One recent Monday, Zach called. He’d been reaching out to an old high school friend who’d lost his mom in the middle of their middle school basketball season years ago. Could he bring him for dinner on Friday? Sure, I said.

On Tuesday, Zach said that a couple of other friends had “heard about” this dinner and wanted to come, too. (One was a guy who’d lived in our garage a few summers ago. I called him “my other boy.”)

On Wednesday, Zach left a voice mail that there’d be two more guys coming, possibly more. He’d let me know. I multiplied my grocery list and bought an extra BBQ grill for all the flat-iron steaks.

Annie, Zach, Taylor and friends on back deck

On Thursday, I invited my parents and cousin for the dinner because it seemed I was suddenly having a party.

On Friday morning Taylor mentioned that a few friends might be coming over. I assumed he meant for afternoon video games but I gave it no more thought because I was too busy chopping and dicing in the kitchen.

On Friday afternoon, Zach’s friends showed up, early. Zach arrived late, went for a run and then took a shower.

At 6 pm, Taylor’s best friend from across the street appeared. I added a chair to the deck table. Soon four more of Taylor’s friends materialized. It dawned on me--Taylor had invited them all for dinner. “Remember, Mom? I told you my friends were coming over?”

We had eighteen for dinner.

December 18th, 1982. Ruth, Jean; Jim, Jean, Grandpa and Grandma Southworth

I moved chairs around, butterflied the steaks to make them appear bigger, and zapped a frozen pasta dish. The boys polished off everything but the fruit salad. After dinner I doubled the homemade ice cream mix using non-fat milk, resulting in a barely-frozen, mashed-potato-like vanilla soup. The hot fudge topping didn’t help the faulty freeze. The boys said it was the best ice cream ever. They may eat a lot, but they are easy to please.

Afterwards we were content but exhausted. I’m relieved I rarely have to cook like that anymore. Actually, I rarely cook like I used to, period. I figure I’ve done my share in the kitchen over the years, and Taylor doesn’t care much. As long as he has a stocked pantry and fridge, he’s a pretty self-sufficient kid. He’ll grill up his steaks and make his sandwiches and happily bypass his parents’ middle-aged, health-conscious diet.

Taylor makes it easy to be a parent, in general. People ask if I’m worried about an empty nest once Taylor leaves for college next year, but I feel like we’re already transitioning. The boy is fairly independent and I’m happy about that; it means I’ve done my job.

Joe and Ruth; Sally (Jim's mom), dog Louie and Jimmy

I’ve got lots of freedom these days. Most of the time, I get to do what I want, when I want. Jim and I are starting to travel more, and our greatest impediment to that is not our kids, but our Labrador. Do I feel guilty? No. I’ve worked hard at my mommy job over the years and feel a great sense of accomplishment in that. Plus, all I have to do is look at old family videos to remind myself of how much energy I expended raising our three children into (largely) autonomous young adults.

Jim’s been organizing some of those family videos into clips for his new Facebook page. (He signed up for Facebook as another tool for staying connected with our kids; the videos are an amusing on-line draw.) Several of our kids’ friends like the videos so much, they invited Jim to become their “friend.” (Taylor hasn’t accepted Dad’s intrusion into his personal space as readily as Zach and Annie.) Jim also posts old photos from my scrapbooks onto Facebook.

The photos and videos are often so comical that we often take them for granted. But our photographic record is fragile and irreplaceable, and it helps link us while keeping our family history alive.

We have little record, photographically or otherwise, of the life of my great-grandmother, Josie, and her journey to eastern Oregon in 1905. Josie died in the desolate hills of Durkee after delivering three babies in four years time. With that one tragic event, Josie’s children lost ties to their mother’s extensive Corvallis family; Josie wasn’t around to maintain the family story and nurture connections.

Nearly one hundred years later, Jim and I reestablished that connection. Last week, we visited the 1840’s farm that Josie’s grandfather crafted in Corvallis. My distant cousin, Tom, lives alone in the old farmhouse now. Tom’s a retired 80-something lawyer who sold the farm four years ago to the city but continues living there as part of a life-estate.

A couple of years ago, Tom turned over some old photos from the farmhouse to the local historical society. Among the collection were pictures of my grandmother, Josie. I was eager to meet Tom, see more photos and revisit my family’s heritage house. I made arrangements through a third cousin for us to stop by.

Tom greeted Jim and me warmly and showed us around his farm with its view of the valley below and the Cascades in the distance. He said he felt lucky to live in such beauty. “That’s Mt. Jefferson! Sometimes you can see Three Sisters over there!”

Tom has difficulty getting around the farm these days. We worried about him falling as we trudged through the property’s blackberry bushes and thick weeds. When we reached the front door of the farmhouse, Tom stopped, smiled, and warned us that he wasn’t much of a housekeeper.

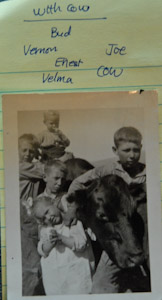

But Tom had prepared for our visit by gathering family photos. He stored them loose and unlabeled in a brown paper garbage sack. Jim took photos of my anonymous ancestors.

The Owens Farm: Jean and Tom

Tom said he’d never married nor had children. He moved to the farm from Medford following his mother’s death 22 years ago. After Tom and his sister sold the farm and house, he thought the city should shoulder repairs and upkeep. But that wasn’t happening. The roof likely leaked and the walls buckled. Jim suspects the city may have to level the house after Tom’s passing. We hope not.

With unsettled spirits, Jim and I said goodbye to this dear old man. Tom wasn’t interested in leaving the farm, but what would happen if he fell? And how had my newly-rediscovered ancestral farmhouse reached such a point of disintegration?

On our way home, we stopped to pick blackberries at Minto-Brown Island Park and mulled over Tom’s life. That’s when Jim began ruminating about matriarchs. He decided that matriarchs are wholly underrated. He argued that in our culture, the patriarchs dominate during their working years, but eventually the matriarchs surpass them in significance. The power shift changes dramatically over time, but people rarely notice it. Unless that mother piece goes missing…

Following the death of my great-grandmother, her children suffered and their Corvallis heritage was lost for generations. With the death of Tom’s mother and the absence of a female presence, the farmhouse suffered.

Matriarchal voids are huge. Left unfilled, they eventually clog with pain, estrangement, deterioration and a sack of unlabeled photographs.

I scraped my arms on thorns of Minto-Brown blackberry bushes, picking and listening while Jim reflected over his teenage years. At age fifteen, his mother suddenly died and his immediate family-life collapsed. But Jim had a saving grace in his grandparents, particularly his grandmother. She was always available to listen, offer encouragement, co-sign his dental school loan, make chocolate milkshakes. Even if all else fell apart, Grandma Lucille was there, steady and loving.

Grandma Cille and Baby Zach

Despite Grandpa Bruce’s blindness and debilitating heart condition, he remained at home; Grandma Lucille rented a hospital bed for their living room. She hired nurses to help and the family rallied around them both. And as long as Lucille was alive, the extended family gathered for holidays. She was the big draw, absolutely.

Were it not for Grandma Lucille, I don’t know if my Jim would have survived to be the man he is today. I owe a lot to Lucille, the matriarch of the Southworth family. Her passing several years ago still leaves a void. She and my mom both make marvelous role models in just how to matriarch.

I’ve decided to lay an early claim on my own matriarchy. I’ll keep our house a home. Assemble photo albums. Answer phones at frightening hours. Offer emotional support and AAA cards. Try to demonstrate flexibility and forgiveness. Make extra flat-iron steak and slushy ice cream.

Our kids and their friends know they can keep coming around. We’ll be here.

I do not fear an empty nest. The nest may go unfilled now and then, but the lives are pretty fulfilled.

I guess it doesn’t really matter so much what I do these days as much as that I simply am. I’m satisfied. It’s a good generational place to be.